/usr/bin/imqbrokerd -vmargs "-Xms256m -Xmx1024m"14 Analyzing and Tuning a Message Service

This chapter covers a number of topics about how to analyze and tune a Message Queue service to optimize the performance of your messaging applications. It includes the following topics:

About Performance

This section provides some background information on performance tuning.

The Performance Tuning Process

The performance you get out of a messaging application depends on the interaction between the application and the Message Queue service. Hence, maximizing performance requires the combined efforts of both the application developer and the administrator.

The process of optimizing performance begins with application design and continues on through tuning the message service after the application has been deployed. The performance tuning process includes the following stages:

-

Defining performance requirements for the application

-

Designing the application taking into account factors that affect performance (especially tradeoffs between reliability and performance)

-

Establishing baseline performance measures

-

Tuning or reconfiguring the message service to optimize performance

The process outlined above is often iterative. During deployment of the application, a Message Queue administrator evaluates the suitability of the message service for the application’s general performance requirements. If the benchmark testing meets these requirements, the administrator can tune the system as described in this chapter. However, if benchmark testing does not meet performance requirements, a redesign of the application might be necessary or the deployment architecture might need to be modified.

Aspects of Performance

In general, performance is a measure of the speed and efficiency with which a message service delivers messages from producer to consumer. However, there are several different aspects of performance that might be important to you, depending on your needs.

- Connection Load

-

The number of message producers, or message consumers, or the number of concurrent connections a system can support.

- Message throughput

-

The number of messages or message bytes that can be pumped through a messaging system per second.

- Latency

-

The time it takes a particular message to be delivered from message producer to message consumer.

- Stability

-

The overall availability of the message service or how gracefully it degrades in cases of heavy load or failure.

- Efficiency

-

The efficiency of message delivery; a measure of message throughput in relation to the computing resources employed.

These different aspects of performance are generally interrelated. If message throughput is high, that means messages are less likely to be backlogged in the broker, and as a result, latency should be low (a single message can be delivered very quickly). However, latency can depend on many factors: the speed of communication links, broker processing speed, and client processing speed, to name a few.

In any case, the aspects of performance that are most important to you generally depends on the requirements of a particular application.

Benchmarks

Benchmarking is the process of creating a test suite for your messaging application and of measuring message throughput or other aspects of performance for this test suite.

For example, you could create a test suite by which some number of producing clients, using some number of connections, sessions, and message producers, send persistent or nonpersistent messages of a standard size to some number of queues or topics (all depending on your messaging application design) at some specified rate. Similarly, the test suite includes some number of consuming clients, using some number of connections, sessions, and message consumers (of a particular type) that consume the messages in the test suite’s physical destinations using a particular acknowledgment mode.

Using your standard test suite you can measure the time it takes between production and consumption of messages or the average message throughput rate, and you can monitor the system to observe connection thread usage, message storage data, message flow data, and other relevant metrics. You can then ramp up the rate of message production, or the number of message producers, or other variables, until performance is negatively affected. The maximum throughput you can achieve is a benchmark for your message service configuration.

Using this benchmark, you can modify some of the characteristics of your test suite. By carefully controlling all the factors that might have an effect on performance (see Application Design Factors Affecting Performance), you can note how changing some of these factors affects the benchmark. For example, you can increase the number of connections or the size of messages five-fold or ten-fold, and note the effect on performance.

Conversely, you can keep application-based factors constant and change your broker configuration in some controlled way (for example, change connection properties, thread pool properties, JVM memory limits, limit behaviors, file-based versus JDBC-based persistence, and so forth) and note how these changes affect performance.

This benchmarking of your application provides information that can be valuable when you want to increase the performance of a deployed application by tuning your message service. A benchmark allows the effect of a change or a set of changes to be more accurately predicted.

As a general rule, benchmarks should be run in a controlled test environment and for a long enough period of time for your message service to stabilize. (Performance is negatively affected at startup by the just-in-time compilation that turns Java code into machine code.)

Baseline Use Patterns

Once a messaging application is deployed and running, it is important to establish baseline use patterns. You want to know when peak demand occurs and you want to be able to quantify that demand. For example, demand normally fluctuates by number of end users, activity levels, time of day, or all of these.

To establish baseline use patterns you need to monitor your message service over an extended period of time, looking at data such as the following:

-

Number of connections

-

Number of messages stored in the broker (or in particular physical destinations)

-

Message flows into and out of a broker (or particular physical destinations)

-

Numbers of active consumers

You can also use average and peak values provided in metrics data.

It is important to check these baseline metrics against design expectations. By doing so, you are checking that client code is behaving properly: for example, that connections are not being left open or that consumed messages are not being left unacknowledged. These coding errors consume broker resources and could significantly affect performance.

The base-line use patterns help you determine how to tune your system for optimal performance. For example:

-

If one physical destination is used significantly more than others, you might want to set higher message memory limits on that physical destination than on others, or to adjust limit behaviors accordingly.

-

If the number of connections needed is significantly greater than allowed by the maximum thread pool size, you might want to increase the thread pool size or adopt a shared thread model.

-

If peak message flows are substantially greater than average flows, that might influence the limit behaviors you employ when memory runs low.

In general, the more you know about use patterns, the better you are able to tune your system to those patterns and to plan for future needs.

Factors Affecting Performance

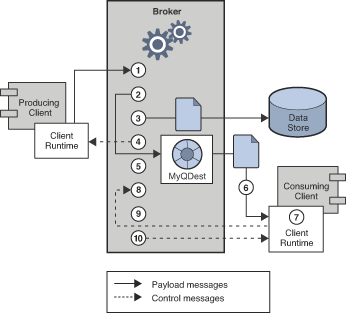

Message latency and message throughput, two of the main performance indicators, generally depend on the time it takes a typical message to complete various steps in the message delivery process. These steps are shown below for the case of a persistent, reliably delivered message. The steps are described following the illustration.

Message Delivery Steps

-

The message is delivered from producing client to broker.

-

The broker reads in the message.

-

The message is placed in persistent storage (for reliability).

-

The broker confirms receipt of the message (for reliability).

-

The broker determines the routing for the message.

-

The broker writes out the message.

-

The message is delivered from broker to consuming client.

-

The consuming client acknowledges receipt of the message (for reliability).

-

The broker processes client acknowledgment (for reliability).

-

The broker confirms that client acknowledgment has been processed.

Since these steps are sequential, any one of them can be a potential bottleneck in the delivery of messages from producing clients to consuming clients. Most of the steps depend on physical characteristics of the messaging system: network bandwidth, computer processing speeds, message service architecture, and so forth. Some, however, also depend on characteristics of the messaging application and the level of reliability it requires.

The following subsections discuss the effect of both application design factors and messaging system factors on performance. While application design and messaging system factors closely interact in the delivery of messages, each category is considered separately.

Application Design Factors Affecting Performance

Application design decisions can have a significant effect on overall messaging performance.

The most important factors affecting performance are those that affect the reliability of message delivery. Among these are the following:

Other application design factors affecting performance are the following:

The sections that follow describe the effect of each of these factors on messaging performance. As a general rule, there is a tradeoff between performance and reliability: factors that increase reliability tend to decrease performance.

Table 14-1 shows how the various application design factors generally affect messaging performance. The table shows two scenarios—one high-reliability, low-performance, and one high-performance, low-reliability—and the choices of application design factors that characterize each. Between these extremes, there are many choices and tradeoffs that affect both reliability and performance.

Table 14-1 Comparison of High-Reliability and High-Performance Scenarios

| Application Design Factor | High-Reliability, Low-Performance Scenario | High-Performance, Low-Reliability Scenario |

|---|---|---|

Delivery mode |

Persistent messages |

Nonpersistent messages |

Use of transactions |

Transacted sessions |

No transactions |

Acknowledgment mode |

|

|

Durable/nondurable subscriptions |

Durable subscriptions |

Nondurable subscriptions |

Use of selectors |

Message filtering |

No message filtering |

Message size |

Large number of small messages |

Small number of large messages |

Message body type |

Complex body types |

Simple body types |

Delivery Mode (Persistent/Nonpersistent Messages)

Persistent messages guarantee message delivery in case of broker failure. The broker stores the message in a persistent store until all intended consumers acknowledge they have consumed the message.

Broker processing of persistent messages is slower than for nonpersistent messages for the following reasons:

-

A broker must reliably store a persistent message so that it will not be lost should the broker fail.

-

The broker must confirm receipt of each persistent message it receives. Delivery to the broker is guaranteed once the method producing the message returns without an exception.

-

Depending on the client acknowledgment mode, the broker might need to confirm a consuming client’s acknowledgment of a persistent message.

For both queues and topics with durable subscribers, performance was

approximately 40% faster for nonpersistent messages. We obtained these

results using 10k-sized messages and AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGE mode.

Use of Transactions

A transaction is a guarantee that all messages produced in a transacted session and all messages consumed in a transacted session will be either processed or not processed (rolled back) as a unit.

Message Queue supports both local and distributed transactions.

A message produced or acknowledged in a transacted session is slower than in a nontransacted session for the following reasons:

-

Additional information must be stored with each produced message.

-

In some situations, messages in a transaction are stored when normally they would not be (for example, a persistent message delivered to a topic destination with no subscriptions would normally be deleted, however, at the time the transaction is begun, information about subscriptions is not available).

-

Information on the consumption and acknowledgment of messages within a transaction must be stored and processed when the transaction is committed.

|

Note

|

To improve performance, Message Queue message brokers are configured by

default to use a memory-mapped file to store transaction data. On file

systems that do not support memory-mapped files, you can disable this

behavior by setting the broker property

|

Acknowledgment Mode

One mechanism for ensuring the reliability of JMS message delivery is for a client to acknowledge consumption of messages delivered to it by the Message Queue broker.

If a session is closed without the client acknowledging the message or

if the broker fails before the acknowledgment is processed, the broker

redelivers that message, setting a JMSRedelivered flag.

For a nontransacted session, the client can choose one of three acknowledgment modes, each of which has its own performance characteristics:

-

AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGE. The system automatically acknowledges a message once the consumer has processed it. This mode guarantees at most one redelivered message after a provider failure. -

CLIENT_ACKNOWLEDGE. The application controls the point at which messages are acknowledged. All messages processed in that session since the previous acknowledgment are acknowledged. If the broker fails while processing a set of acknowledgments, one or more messages in that group might be redelivered. -

DUPS_OK_ACKNOWLEDGE. This mode instructs the system to acknowledge messages in a lazy manner. Multiple messages can be redelivered after a provider failure.

(Using CLIENT_ACKNOWLEDGE mode is similar to using transactions,

except there is no guarantee that all acknowledgments will be processed

together if a provider fails during processing.)

Acknowledgment mode affects performance for the following reasons:

-

Extra control messages between broker and client are required in

AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGEandCLIENT_ACKNOWLEDGEmodes. The additional control messages add additional processing overhead and can interfere with JMS payload messages, causing processing delays. -

In

AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGEandCLIENT_ACKNOWLEDGEmodes, the client must wait until the broker confirms that it has processed the client’s acknowledgment before the client can consume additional messages. (This broker confirmation guarantees that the broker will not inadvertently redeliver these messages.) -

The Message Queue persistent store must be updated with the acknowledgment information for all persistent messages received by consumers, thereby decreasing performance.

Durable and Nondurable Subscriptions

Subscribers to a topic destination fall into two categories, those with durable and nondurable subscriptions.

Durable subscriptions provide increased reliability but slower throughput, for the following reasons:

-

The Message Queue message service must persistently store the list of messages assigned to each durable subscription so that should a broker fail, the list is available after recovery.

-

Persistent messages for durable subscriptions are stored persistently, so that should a broker fail, the messages can still be delivered after recovery, when the corresponding consumer becomes active. By contrast, persistent messages for nondurable subscriptions are not stored persistently (should a broker fail, the corresponding consumer connection is lost and the message would never be delivered).

We compared performance for durable and nondurable subscribers in two

cases: persistent and nonpersistent 10k-sized messages. Both cases use

AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGE acknowledgment mode. We found an effect on

performance only in the case of persistent messages which slowed

durables by about 30%

Use of Selectors (Message Filtering)

Application developers often want to target sets of messages to particular consumers. They can do so either by targeting each set of messages to a unique physical destination or by using a single physical destination and registering one or more selectors for each consumer.

A selector is a string requesting that only messages with property

values that match the string are delivered to a particular consumer. For

example, the selector NumberOfOrders>1 delivers only the messages with

a NumberOfOrders property value of 2 or more.

Creating consumers with selectors lowers performance (as compared to using multiple physical destinations) because additional processing is required to handle each message. When a selector is used, it must be parsed so that it can be matched against future messages. Additionally, the message properties of each message must be retrieved and compared against the selector as each message is routed. However, using selectors provides more flexibility in a messaging application.

Message Size

Message size affects performance because more data must be passed from producing client to broker and from broker to consuming client, and because for persistent messages a larger message must be stored.

However, by batching smaller messages into a single message, the routing and processing of individual messages can be minimized, providing an overall performance gain. In this case, information about the state of individual messages is lost.

In our tests, which compared throughput in kilobytes per second for 1k,

10k, and 100k-sized messages to a queue destination and

AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGE acknowledgment mode, we found that nonpersistent

messaging was about 50% faster for 1k messages, about 20% faster for 10k

messages, and about 5% faster for 100k messages. The size of the message

affected performance significantly for both persistent and nonpersistent

messages. 100k messages are about 10 times faster than 10k, and 10k are

about 5 times faster than 1k.

Message Body Type

JMS supports five message body types, shown below roughly in the order of complexity:

-

BytesMessagecontains a set of bytes in a format determined by the application. -

TextMessageis a simple Java string. -

StreamMessagecontains a stream of Java primitive values. -

MapMessagecontains a set of name-value pairs. -

ObjectMessagecontains a Java serialized object.

While, in general, the message type is dictated by the needs of an

application, the more complicated types (MapMessage and

ObjectMessage) carry a performance cost: the expense of serializing

and deserializing the data. The performance cost depends on how simple

or how complicated the data is.

Message Service Factors Affecting Performance

The performance of a messaging application is affected not only by application design, but also by the message service performing the routing and delivery of messages.

The following sections discuss various message service factors that can affect performance. Understanding the effect of these factors is key to sizing a message service and diagnosing and resolving performance bottlenecks that might arise in a deployed application.

The most important factors affecting performance in a Message Queue service are the following:

The sections below describe the effect of each of these factors on messaging performance.

Hardware

For both the Message Queue broker and client applications, CPU processing speed and available memory are primary determinants of message service performance. Many software limitations can be eliminated by increasing processing power, while adding memory can increase both processing speed and capacity. However, it is generally expensive to overcome bottlenecks simply by upgrading your hardware.

Operating System

Because of the efficiencies of different operating systems, performance can vary, even assuming the same hardware platform. For example, the thread model employed by the operating system can have an important effect on the number of concurrent connections a broker can support. In general, all hardware being equal, Solaris is generally faster than Linux, which is generally faster than Windows.

Java Virtual Machine (JVM)

The broker is a Java process that runs in and is supported by the host JVM. As a result, JVM processing is an important determinant of how fast and efficiently a broker can route and deliver messages.

In particular, the JVM’s management of memory resources can be critical. Sufficient memory has to be allocated to the JVM to accommodate increasing memory loads. In addition, the JVM periodically reclaims unused memory, and this memory reclamation can delay message processing. The larger the JVM memory heap, the longer the potential delay that might be experienced during memory reclamation.

Connections

The number and speed of connections between client and broker can affect the number of messages that a message service can handle as well as the speed of message delivery.

Broker Connection Limits

All access to the broker is by way of connections. Any limit on the number of concurrent connections can affect the number of producing or consuming clients that can concurrently use the broker.

The number of connections to a broker is generally limited by the number of threads available. Message Queue can be configured to support either a dedicated thread model or a shared thread model (see Thread Pool Management).

The dedicated thread model is very fast because each connection has dedicated threads, however the number of connections is limited by the number of threads available (one input thread and one output thread for each connection). The shared thread model places no limit on the number of connections, however there is significant overhead and throughput delays in sharing threads among a number of connections, especially when those connections are busy.

Transport Protocols

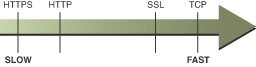

Message Queue software allows clients to communicate with the broker using various low-level transport protocols. Message Queue supports the connection services (and corresponding protocols) described in Configuring Connection Services.

The choice of protocols is based on application requirements (encrypted, accessible through a firewall), but the choice affects overall performance.

Our tests compared throughput for TCP and SSL for two cases: a

high-reliability scenario (1k persistent messages sent to topic

destinations with durable subscriptions and using AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGE

acknowledgment mode) and a high-performance scenario (1k nonpersistent

messages sent to topic destinations without durable subscriptions and

using DUPS_OK_ACKNOWLEDGE acknowledgment mode).

In general we found that protocol has less effect in the high-reliability case. This is probably because the persistence overhead required in the high-reliability case is a more important factor in limiting throughput than the protocol speed. Additionally:

-

TCP provides the fastest method to communicate with the broker.

-

SSL is 50 to 70 percent slower than TCP when it comes to sending and receiving messages (50 percent for persistent messages, closer to 70 percent for nonpersistent messages). Additionally, establishing the initial connection is slower with SSL (it might take several seconds) because the client and broker (or Web Server in the case of HTTPS) need to establish a private key to be used when encrypting the data for transmission. The performance drop is caused by the additional processing required to encrypt and decrypt each low-level TCP packet.

-

HTTP is slower than either the TCP or SSL. It uses a servlet that runs on a Web server as a proxy between the client and the broker. Performance overhead is involved in encapsulating packets in HTTP requests and in the requirement that messages go through two hops—client to servlet, servlet to broker—to reach the broker.

-

HTTPS is slower than HTTP because of the additional overhead required to encrypt the packet between client and servlet and between servlet and broker.

Message Service Architecture

A Message Queue message service can be implemented as a single broker or as a cluster consisting of multiple interconnected broker instances.

As the number of clients connected to a broker increases, and as the number of messages being delivered increases, a broker will eventually exceed resource limitations such as file descriptor, thread, and memory limits. One way to accommodate increasing loads is to add more broker instances to a Message Queue message service, distributing client connections and message routing and delivery across multiple brokers.

In general, this scaling works best if clients are evenly distributed across the cluster, especially message producing clients. Because of the overhead involved in delivering messages between the brokers in a cluster, clusters with limited numbers of connections or limited message delivery rates, might exhibit lower performance than a single broker.

You might also use a broker cluster to optimize network bandwidth. For example, you might want to use slower, long distance network links between a set of remote brokers within a cluster, while using higher speed links for connecting clients to their respective broker instances.

For more information on clusters, see Configuring and Managing Broker Clusters

Broker Limits and Behaviors

The message throughput that a broker might be required to handle is a function of the use patterns of the messaging applications the broker supports. However, the broker is limited in resources: memory, CPU cycles, and so forth. As a result, it would be possible for a broker to become overwhelmed to the point where it becomes unresponsive or unstable.

The Message Queue message broker has mechanisms built in for managing memory resources and preventing the broker from running out of memory. These mechanisms include configurable limits on the number of messages or message bytes that can be held by a broker or its individual physical destinations, and a set of behaviors that can be instituted when physical destination limits are reached.

With careful monitoring and tuning, these configurable mechanisms can be used to balance the inflow and outflow of messages so that system overload cannot occur. While these mechanisms consume overhead and can limit message throughput, they nevertheless maintain operational integrity.

Data Store Performance

Message Queue supports both file-based and JDBC-based persistence modules. File-based persistence uses individual files to store persistent data. JDBC-based persistence uses a Java Database Connectivity (JDBC) interface and requires a JDBC-compliant data store. File-based persistence is generally faster than JDBC-based; however, some users prefer the redundancy and administrative control provided by a JDBC-compliant store.

In the case of file-based persistence, you can maximize reliability by specifying that persistence operations synchronize the in-memory state with the data store. This helps eliminate data loss due to system crashes, but at the expense of performance.

Client Runtime Configuration

The Message Queue client runtime provides client applications with an interface to the Message Queue message service. It supports all the operations needed for clients to send messages to physical destinations and to receive messages from such destinations. The client runtime is configurable (by setting connection factory attribute values), allowing you to control aspects of its behavior, such as connection flow metering, consumer flow limits, and connection flow limits, that can improve performance and message throughput. See Client Runtime Message Flow Adjustments for more information on these features and the attributes used to configure them.

Adjusting Configuration To Improve Performance

The following sections explain how configuration adjustments can affect performance.

System Adjustments

The following sections describe adjustments you can make to the operating system, JVM, communication protocols, and persistent data store.

Solaris Tuning: CPU Utilization, Paging/Swapping/Disk I/O

See your system documentation for tuning your operating system.

Java Virtual Machine Adjustments

By default, the broker uses a JVM heap size of 192MB. This is often too small for significant message loads and should be increased.

When the broker gets close to exhausting the JVM heap space used by Java objects, it uses various techniques such as flow control and message swapping to free memory. Under extreme circumstances it even closes client connections in order to free the memory and reduce the message inflow. Hence it is desirable to set the maximum JVM heap space high enough to avoid such circumstances.

However, if the maximum Java heap space is set too high, in relation to system physical memory, the broker can continue to grow the Java heap space until the entire system runs out of memory. This can result in diminished performance, unpredictable broker crashes, and/or affect the behavior of other applications and services running on the system. In general, you need to allow enough physical memory for the operating system and other applications to run on the machine.

In general it is a good idea to evaluate the normal and peak system memory footprints, and configure the Java heap size so that it is large enough to provide good performance, but not so large as to risk system memory problems.

To change the minimum and maximum heap size for the broker, use the

-vmargs command line option when starting the broker. For example:

This command will set the starting Java heap size to 256MB and the maximum Java heap size to 1GB.

-

On Solaris or Linux, if starting the broker via

/etc/rc*(that is,/etc/init.d/imq), specify broker command line arguments in the file/etc/imq/imqbrokerd.conf(Solaris) or/etc/opt/sun/mq/imqbrokerd.conf(Linux). See the comments in that file for more information. -

On Windows, if starting the broker as a Window’s service, specify JVM arguments using the

-vmargsoption to theimqsvcadmininstallcommand. See Service Administrator Utility.

In any case, verify settings by checking the broker’s log file or using

the imqcmd metrics bkr -m cxn command.

Tuning Transport Protocols

Once a protocol that meets application needs has been chosen, additional tuning (based on the selected protocol) might improve performance.

A protocol’s performance can be modified using the following three broker properties:

-

imq.protocol.`protocolType.nodelay` -

imq.protocol.`protocolType.inbufsz` -

imq.protocol.`protocolType.outbufsz`

For TCP and SSL protocols, these properties affect the speed of message delivery between client and broker. For HTTP and HTTPS protocols, these properties affect the speed of message delivery between the Message Queue tunnel servlet (running on a Web server) and the broker. For HTTP/ HTTPS protocols there are additional properties that can affect performance (see HTTP/HTTPS Tuning).

The protocol tuning properties are described in the following sections.

nodelay

The nodelay property affects Nagle’s algorithm (the value of the

TCP_NODELAY socket-level option on TCP/IP) for the given protocol.

Nagle’s algorithm is used to improve TCP performance on systems using

slow connections such as wide-area networks (WANs).

When the algorithm is used, TCP tries to prevent several small chunks of data from being sent to the remote system (by bundling the data in larger packets). If the data written to the socket does not fill the required buffer size, the protocol delays sending the packet until either the buffer is filled or a specific delay time has elapsed. Once the buffer is full or the timeout has occurred, the packet is sent.

For most messaging applications, performance is best if there is no delay in the sending of packets (Nagle’s algorithm is not enabled). This is because most interactions between client and broker are request/response interactions: the client sends a packet of data to the broker and waits for a response. For example, typical interactions include:

-

Creating a connection

-

Creating a producer or consumer

-

Sending a persistent message (the broker confirms receipt of the message)

-

Sending a client acknowledgment in an

AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGEorCLIENT_ACKNOWLEDGEsession (the broker confirms processing of the acknowledgment)

For these interactions, most packets are smaller than the buffer size. This means that if Nagle’s algorithm is used, the broker delays several milliseconds before sending a response to the consumer.

However, Nagle’s algorithm may improve performance in situations where

connections are slow and broker responses are not required. This would

be the case where a client sends a nonpersistent message or where a

client acknowledgment is not confirmed by the broker

(DUPS_OK_ACKNOWLEDGE session).

inbufsz/outbufsz

The inbufsz property sets the size of the buffer on the input stream

reading data coming in from a socket. Similarly, outbufsz sets the

buffer size of the output stream used by the broker to write data to the

socket.

In general, both parameters should be set to values that are slightly

larger than the average packet being received or sent. A good rule of

thumb is to set these property values to the size of the average packet

plus 1 kilobyte (rounded to the nearest kilobyte). For example, if the

broker is receiving packets with a body size of 1 kilobyte, the overall

size of the packet (message body plus header plus properties) is about

1200 bytes; an inbufsz of 2 kilobytes (2048 bytes) gives reasonable

performance. Increasing inbufsz or outbufsz greater than that size

may improve performance slightly, but increases the memory needed for

each connection.

HTTP/HTTPS Tuning

In addition to the general properties discussed in the previous two sections, HTTP/HTTPS performance is limited by how fast a client can make HTTP requests to the Web server hosting the Message Queue tunnel servlet.

A Web server might need to be optimized to handle multiple requests on a single socket. With JDK version 1.4 and later, HTTP connections to a Web server are kept alive (the socket to the Web server remains open) to minimize resources used by the Web server when it processes multiple HTTP requests. If the performance of a client application using JDK version 1.4 is slower than the same application running with an earlier JDK release, you might need to tune the Web server keep-alive configuration parameters to improve performance.

In addition to such Web server tuning, you can also adjust how often a

client polls the Web server. HTTP is a request-based protocol. This

means that clients using an HTTP-based protocol periodically need to

check the Web server to see if messages are waiting. The

imq.httpjms.http.pullPeriod broker property (and the corresponding

imq.httpsjms.https.pullPeriod property) specifies how often the

Message Queue client runtime polls the Web server.

If the pullPeriod value is -1 (the default value), the client

runtime polls the server as soon as the previous request returns,

maximizing the performance of the individual client. As a result, each

client connection monopolizes a request thread in the Web server,

possibly straining Web server resources.

If the pullPeriod value is a positive number, the client runtime

periodically sends requests to the Web server to see if there is pending

data. In this case, the client does not monopolize a request thread in

the Web server. Hence, if large numbers of clients are using the Web

server, you might conserve Web server resources by setting the

pullPeriod to a positive value.

Tuning the File-based Persistent Store

For information on tuning the file-based persistent store, see Configuring a File-Based Data Store.

Broker Memory Management Adjustments

You can improve performance and increase broker stability under load by properly managing broker memory. Memory management can be configured on a destination-by-destination basis or on a system-wide level (for all destinations, collectively).

Using Physical Destination Limits

To configure physical destination limits, see the properties described in Physical Destination Properties.

Using System-Wide Limits

If message producers tend to overrun message consumers, messages can accumulate in the broker. The broker contains a mechanism for throttling back producers and swapping messages out of active memory under low memory conditions, but it is wise to set a hard limit on the total number of messages (and message bytes) that the broker can hold.

Control these limits by setting the imq.system.max_count and the

imq.system.max_size broker properties.

For example:

imq.system.max_count=5000The defined value above means that the broker will only hold up to 5000 undelivered and/or unacknowledged messages. If additional messages are sent, they are rejected by the broker. If a message is persistent then the clinet runtime will throw an exception when the producer tries to send the message. If the message is non-persistent, the broker silently drops the message.

When an exception is thrown in sending a message, the client should process the exception by pausing for a moment and retrying the send again. (Note that the exception will never be due to the broker’s failure to receive a message; the exception is thrown by the client runtime before the message is sent to the broker.)

Client Runtime Message Flow Adjustments

This section discusses client runtimeflow control behaviors that affect performance. These behaviors are configured as attributes of connection factory administered objects. For information on setting connection factory attributes, see Managing Administered Objects.

Message Flow Metering

Messages sent and received by clients (payload messages), as well as Message Queue control messages, pass over the same client-broker connection. Delays in the delivery of control messages, such as broker acknowledgments, can result if control messages are held up by the delivery of payload messages. To prevent this type of congestion, Message Queue meters the flow of payload messages across a connection.

Payload messages are batched (as specified with the connection factory

attribute imqConnectionFlowCount) so that only a set number are

delivered. After the batch has been delivered, delivery of payload

messages is suspended and only pending control messages are delivered.

This cycle repeats, as additional batches of payload messages are

delivered followed by pending control messages.

The value of imqConnectionFlowCount should be kept low if the client

is doing operations that require many responses from the broker: for

example, if the client is using CLIENT_ACKNOWLEDGE or

AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGE mode, persistent messages, transactions, or queue

browsers, or is adding or removing consumers. If, on the other hand, the

client has only simple consumers on a connection using

DUPS_OK_ACKNOWLEDGE mode, you can increase imqConnectionFlowCount

without compromising performance.

Message Flow Limits

There is a limit to the number of payload messages that the Message Queue client runtime can handle before encountering local resource limitations, such as memory. When this limit is approached, performance suffers. Hence, Message Queue lets you limit the number of messages per consumer (or messages per connection) that can be delivered over a connection and buffered in the client runtime, waiting to be consumed.

Consumer Flow Limits

When the number of payload messages delivered to the client runtime

exceeds the value of imqConsumerFlowLimit for any consumer, message

delivery for that consumer stops. It is resumed only when the number of

unconsumed messages for that consumer drops below the value set with

imqConsumerFlowThreshold.

The following example illustrates the use of these limits: consider the default settings for topic consumers:

imqConsumerFlowLimit=1000

imqConsumerFlowThreshold=50When the consumer is created, the broker delivers an initial batch of

1000 messages (providing they exist) to this consumer without pausing.

After sending 1000 messages, the broker stops delivery until the client

runtime asks for more messages. The client runtime holds these messages

until the application processes them. The client runtime then allows the

application to consume at least 50% (imqConsumerFlowThreshold ) of the

message buffer capacity (i.e. 500 messages) before asking the broker to

send the next batch.

In the same situation, if the threshold were 10%, the client runtime would wait for the application to consume at least 900 messages before asking for the next batch.

The next batch size is calculated as follows:

imqConsumerFlowLimit - (current number of pending msgs in buffer)So if imqConsumerFlowThreshold is 50%, the next batch size can

fluctuate between 500 and 1000, depending on how fast the application

can process the messages.

If the imqConsumerFlowThreshold is set too high (close to 100%), the

broker will tend to send smaller batches, which can lower message

throughput. If the value is set too low (close to 0%), the client may be

able to finish processing the remaining buffered messages before the

broker delivers the next set, again degrading message throughput.

Generally speaking, unless you have specific performance or reliability

concerns, you will not need to change the default value of

imqConsumerFlowThreshold attribute.

The consumer-based flow controls (in particular, imqConsumerFlowLimit

) are the best way to manage memory in the client runtime. Generally,

depending on the client application, you know the number of consumers

you need to support on any connection, the size of the messages, and the

total amount of memory that is available to the client runtime.

|

Note

|

Setting the |

When the JMS resource adapter, jmsra, is used to consume messages in a GlassFish Server cluster, this behavior is defined using different properties, as described in About Shared Topic Subscriptions for Clustered Containers.

Connection Flow Limits

In the case of some client applications, however, the number of consumers may be indeterminate, depending on choices made by end users. In those cases, you can still manage memory using connection-level flow limits.

Connection-level flow controls limit the total number of messages

buffered for all consumers on a connection. If this number exceeds the

value of imqConnectionFlowLimit, delivery of messages through the

connection stops until that total drops below the connection limit. (The

imqConnectionFlowLimit attribute is enabled only if you set

imqConnectionFlowLimitEnabled to true.)

The number of messages queued up in a session is a function of the number of message consumers using the session and the message load for each consumer. If a client is exhibiting delays in producing or consuming messages, you can normally improve performance by redesigning the application to distribute message producers and consumers among a larger number of sessions or to distribute sessions among a larger number of connections.

Adjusting Multiple-Consumer Queue Delivery

The efficiency with which multiple queue consumers process messages in a queue destination depends on a number of factors. To achieve optimal message throughput there must be a sufficient number of consumers to keep up with the rate of message production for the queue, and the messages in the queue must be routed and then delivered to the active consumers in such a way as to maximize their rate of consumption.

The message delivery mechanism for multiple-consumer queues is that

messages are delivered to consumers in batches as each consumer is ready

to receive a new batch. The readiness of a consumer to receive a batch

of messages depends upon configurable client runtime properties, such as

imqConsumerFlowLimit and imqConsumerFlowThreshold, as described in

Message Flow Limits. As new consumers are added to a queue,

they are sent a batch of messages to consume, and receive subsequent

batches as they become ready.

|

Note

|

The message delivery mechanism for multiple-consumer queues described above can result in messages being consumed in an order different from the order in which they are produced. |

If messages are accumulating in the queue, it is possible that there is

an insufficient number of consumers to handle the message load. It is

also possible that messages are being delivered to consumers in batch

sizes that cause messages to be backing up on the consumers. For

example, if the batch size (consumerFlowLimit) is too large, one

consumer might receive all the messages in a queue while other consumers

receive none. If consumers are very fast, this might not be a problem.

However, if consumers are relatively slow, you want messages to be

distributed to them evenly, and therefore you want the batch size to be

small. Although smaller batch sizes require more overhead to deliver

messages to consumers, for slow consumers there is generally a net

performance gain in using small batch sizes. The value of

consumerFlowLimit can be set on a destination as well as on the client

runtime: the smaller value overrides the larger one.